It is deeply troubling that the USA’s new health secretary believes in conspiracy theories and is hostile towards modern medicine.

Index on Censorship, April 23, 2025.

Challenging the ‘Great Reset’ theory of pandemics

Few events are as compelling as an epidemic. When sufficiently severe, an epidemic evokes responses from every sector of society, laying bare social and economic fault lines and presenting politicians with fraught medical and moral choices. In the most extreme cases, an epidemic can foment a full-blown political crisis.

In 1918 face masks were rmandatory for police officers in San Francisco

Spanish influenza redux: revisiting the mother of all pandemics

The Spanish influenza virus—or at least its viral offspring—have been circulating between the northern and southern hemispheres for 100 years now, but it is arguably only in the past few years that histories of the pandemic virus have achieved a similar ubiquity in our culture.

The Contagious Moment

As the credits roll at the end of Rise of the Planet of the Apes a plane carrying a pilot infected with a deadly brain virus traverses the screen. The pilot has already coughed blood in the departure terminal of San Francisco International airport so we know the prognosis for mankind is not good, and as the plane traces a path between New York, Frankfurt and destinations beyond it isn't long before the globe is ensnared in a web of inter-connecting lines.

The Aids Memorial Qult: each of the nearly 1,920 panels is dedicated to a vicitm of the pandemic

Remembering Aids, Forgetting Flu

Books, music and artworks help us remember the victims of pandemics and imprint the events in our collective memories. But while there are plenty of memorials to AIDS, this was not the case for the 1918 Spanish flu - a pandemic which, seemingly, left far feinter emotional and cultural traces.

Ebola: epidemic Echoes and the Chronicle of A death fortold

Ebola, like other epidemics, seems to draw on a familiar store of images and metaphors—of parasites and hot zones, desperate patients, and intrepid disease detectives. But if Ebola echoes earlier epidemics, which ones? And what can the parallels with those earlier epidemics tell us about the closing scenes of the current outbreak of Ebola?

Lancet, 12 October 2020

Vaccines: inoculating ignorance

Around the world, vaccines are in retreat, shunned by populations who, for the most part, have never been exposed to the diseases that blighted or shortened the lives of their grandparents’ generation. But with the possible exception of quinine – for centuries the only treatment for malaria – and antibiotics, vaccines have saved more lives than any other intervention in medical history.

Antibiotic antagonist: the curious career of René Dubos

The history of antibiotics is usually told as triumph followed by tragedy. First comes the bold promise of the sulpha drugs, then the dawning of the antibiotic era proper; then the sobering realisation that these wonder drugs could have an expiry date. Only rarely do historians mention another miracle drug, gramicidin, and the Rockefeller researcher who discovered it, René Dubos.

Legionnaires’ Disease: the ‘puzzle of the Century’

In 1976, a mysterious disease sickened and killed scores of veterans at an American Legion convention in Philadelphia. Initially mistaken for swine flu - and later blamed on anti-war radicals - the outbreak was eventually traced to an organism that breeds in aquatic environments, including the water towers of hotels and other large buildings.

Disease X + Other Unknowns

In 2018, recognising that a “serious international epidemic could be caused by a pathogen currently unknown to cause human disease”, WHO added a new category to its emergency priority list: Disease X. In the taxonomy of knowledge, Disease X corresponds to what the former US Secretary of State Donald Rumsfeld infamously termed an “unknown unknown”. A classic example is HIV/AIDS. However, AIDS was not the first time a previously unknown pathogen had caught scientists unaware.

Remembering Pandemics Now… and Then

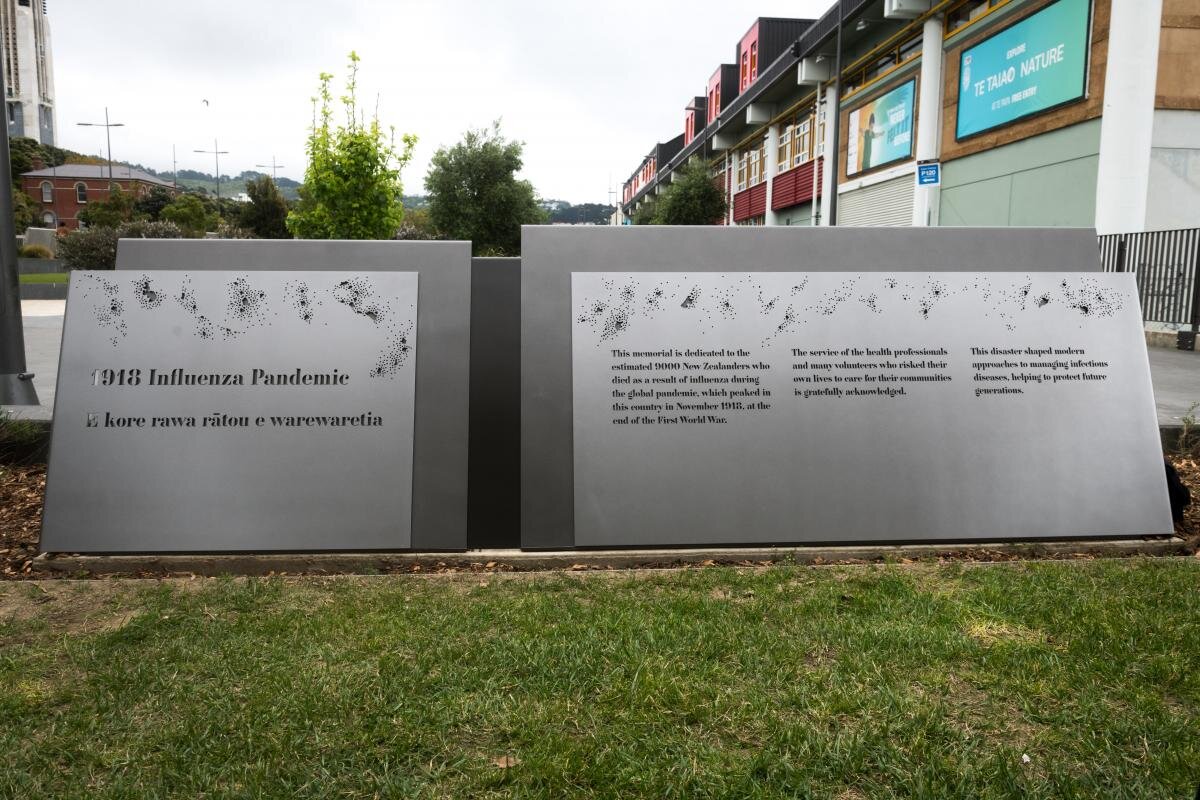

“We erect monuments so that we shall always remember and build memorials so that we shall never forget. But how can we commemorate grief on the scale of Covid-19? And what sort of memorial might make sense of our collective suffering?”

The 1918 Influenza Pandemic Memorial Plaque at Pukehau National War Memorial Park, in Wellington, New Zealand. The plaque was unveiled by New Zealand’s Prime MInister Jacinda Ahern on November 6, 2019 – 55 days before the first report of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, in central China.

In a recurring lockdown dream my father sits at his desk, illuminated by a half-light. My father died in 2004 aged 77 but in my dream it is as if he has merely been absent for a while and has now returned. This absence is never explained however, and when I awake his presence is palpable.

Whether or not we have lost a close family member or friend to Covid-19, we are all haunted by ghosts now: the postman permanently missing from his round; the shop assistant who will never again ask, “is that all?’; or – in my case –my absent but eerily present father.

A year into this dreadful pandemic, the coronavirus has left a void in all our communities, reminding us of griefs present and past. It is a vacuum that cries out to be filled. But how can we commemorate grief on such a scale? And what sort of memorial might make sense of our collective suffering and what Joan Didion calls “the unending absence that follows”?

A little over hundred years ago, when a similarly devastating pandemic swept the British Isles, no one thought to ask these questions. The Spanish influenza pandemic, wrote The Times in 1920, “came and went, a hurricane across the green fields of life… leaving behind it a toll of sickness and infirmity which will not be reckoned in this generation”.

It is unthinkable that the coronavirus pandemic, which at time of writing has claimed the lives of in excess of 120,000 Britons, might suffer a similar fate. Unlike the Spanish flu, which was overshadowed by the First World War, there is no war raging in Europe today. And thanks to the weekly Downing Street coronavirus briefings, no one can be ignorant of the mounting death count. Unlike in 1918, when there was no Chief Medical Officer to share the grim statistics with us – and no television or social media to amplify them - we have followed this “toll of sickness and infirmity” in real time.

Currently, proposals for marking the pandemic include an on-line book of remembrance at St Paul’s Cathedral and a Forest of Memories, with a tree planted for every life lost in the UK because of Covid-19. London Mayor Sadiq Khan is also planning to plant trees in a new public garden at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, 33 for every London borough hit by Covid.

In addition, there have been calls for a monument to Captain Sir Tom to be erected in Westminster and on the anniversary of the first national lockdown on March 23, the Marie Curie Foundation is calling for a National Day of Reflection when families and others bereaved by the pandemic will be encouraged to place daffodils in their windows and light candles.

“We need to mark the huge amount of loss we’ve seen this year and show support for everyone who has been bereaved in the most challenging of circumstances,” says the foundation’s chief executive Mark Reed.

But monuments and memorials serve very different purposes. As the art critic Arthur Danto reminds us: “We erect monuments so that we shall always remember and build memorials so that we shall never forget… Memorials ritualize remembrance and mark the reality of ends.”

Danto was writing about the Vietnam War memorial which, unusually for war memorials, names all 58,000 who died or went missing in the conflict. By contrast, the Cenotaph – from the Greek kenotaphion, meaning “empty tomb” - makes no reference to the individual soldiers who perished fighting the Germans in the First World War. Instead, it symbolises all the “glorious dead” and, arguably, is all the more powerful for it.

But what of an invisible enemy that has bathed the nation in the opposite of glory? As Nazir Afzal, the former Chief Crown Prosecutor for the North West England, tweeted on the day that the US President Joe Biden, held a memorial service at the National Cathedral in Washington DC to mark the 500,000th American victim of the pandemic: “The UK has proportionately lost more of its citizens, no bell ringing, no lowered flags, no remembrance. No accountability… yet”

For Afzal and other critics of the government’s botched pandemic response, such as Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice UK, it is too soon to talk about memorials or monuments. Instead, the group, which represents 2,500 people who have lost a relative to the coronavirus, would like to see a judge-led public inquiry on the model of Hillsborough and Grenfell. In particular, they want to interrogate Boris Johnson’s promise last May that the government would have a “world beating” test-and-trace system in place by the summer and examine key government decisions, such as the discharge of elderly people back into care homes in April. According to Chaand Nagpaul, the chair of the British Medical Association: “A full public inquiry is the only way to determine how effectively public money has been deployed, and what needs to change to ensure we can be best prepared for any future pandemic and properly safeguard the health of the nation.”

However, though in November campaigners beamed messages from bereaved family members onto the Palace of Westminster, Boris Johnson has refused to meet with the group and, so far, just 205,000 people have signed a petition demanding he set a date for the inquiry. Indeed, judging by the latest opinion polls, which put the Conservatives just ahead of Labour, it’s as if in the rush to get vaccinated and resume “normal” life, the British public have already forgiven Johnson’s earlier ineptitude and serial blunders.

Or perhaps, we are simply incapable of imagining the magnitude of the suffering? At time of writing, in excess of 2.5 million people have died of Covid-19 worldwide. But as Albert Camus writes in his novel, The Plague, deaths of this order are “just a mist drifting through the imagination.”

Another reason, as Jonathan Freedland recently observed in The Guardian, is that despite our efforts to anthropomorphise the virus, and for all Johnson’s appeal to military metaphors, SARS-Cov-2 is an “invisible and faceless” foe. The pandemic also lacks a conventional narrative arc, with “clear heroes and villains”. Nor, with the exception of the Chinese, has Covid-19 seen the stigmatization of particular ethnic, religious or social groups.

This was not the case with the 14th century Black Death, which was blamed on Jews, or HIV/Aids, which, despite being widely sexually transmissible, was initially branded a “gay plague”. And it was precisely because homosexuals were shunned and barred from schools and places of work and worship that activists insisted on recalling the injustice by marching on Washington to unveil the Aids Memorial Quilt.

Covid-19, like the 1918 Spanish flu, is not stigmatizing in that way. Nor does it lend itself to moralising. Nonetheless, there is an urgent moral story to be told. That story begins with the recognition that blacks and other ethnic minorities have been dying of Covid-19 at three to four times the rates of whites and go on to interrogate why it is that NHS health workers – one fifth of whom hail from BAME backgrounds – have proved so much more vulnerable to Covid-19 than health workers in other countries.

It is a story that would go on to examine why, despite Matt Hancock’s promise to throw a “protective ring” around the elderly, UK care homes registered in excess of 66,000 deaths between March and June 2020, giving the UK the second worst record in Europe. And it would examine why Britain was so slow to order personal protective equipment (PPE) for doctors and other frontline health workers, such as Dr Abdul Mabud Chowdhury, a 53-year-old consultant urologist at the Homerton hospital in Hackney who died of Covid in April shortly after an issuing an appeal on Facebook for the government to provide “appropriate PPE”.

We need to remember these stories if we are to learn from our mistakes and prevent them happening again. As the political scientist Katherine Hite writes in her book, Politics and the Art of Commemoration, one of the functions of memorials is to “transform the meanings of the past and mobilize the present”.

A good example is the plaque in Pukehau National War Memorial Park, in Wellington, New Zealand, commemorating the country’s experience of Spanish influenza. A rare example of a memorial to the pandemic, the plaque features a graphic representation of the flu’s impact on New Zealand’s north and south islands and acknowledges “the service” of the health workers and many volunteers who risked their lives to provide care to their communities.

More than 9,000 New Zealanders, including 2,500 Maoris, perished in the pandemic, in part because New Zealand failed to act as decisively as Australia, which in October 1918 imposed a strict maritime quarantine on troops returning from the war in Europe. The plaque is the brainchild of Geoffrey Rice, a historian who has written several books about the Spanish flu’s impact on New Zealand, and was unveiled by the country’s prime minister, Jacinda Ahern, on November 6, 2019 – 55 days before the first report of the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan.

To date, New Zealand has recorded just 26 deaths from Covid-19 and has largely eliminated community transmission of the coronavirus – evidence of how the memory of past pandemics can mobilise decisive action in the present. As we look to the social, emotional and cultural challenges that lie ahead of us in the new landscape, we should make full use of the tools of history and resist the amnesiac trance that is the virus’s best hope of retaining its long-term grip upon us.

This essay first appeared in Tortoise on March 12, 2021.